The ROS Command Line Interface

The ROS command line interface, or CLI for short, is a set of programs for starting, inspecting, controlling, and monitoring a ROS robot. The best way to think of the CLI is a collection of small and simple programs that allow you perform basic tasks in ROS. Drawing from our car analogy, the CLI can be thought of as the subsystems of a vehicle: the breaks, the transmission, the window wipers, all of the smaller parts that are composed together to build the larger vehicle. What we'll show you in this section is how to turn on the car, put it in gear, turn on the radio, and perhaps check your oil to perform routine maintenance. The ROS 2 CLI draws heavily from the Unix/Linux philosophy of small programs that can be composed together. If you are familiar with the command line interface found in Unix and Linux, or to a lesser extent in MacOS or Windows, you'll feel right at home.

The ROS command line tools draw heavily from the design patterns mentioned in the previous section, and directly interface with the APIs we will address in the next section. The CLI interface is at its core just a set of simple tools built from the ROS 2 API; this API is simply an implementation of the high-level patterns we discussed in the previous section. If your goal is to simply interface with a particular piece of software written using ROS, the CLI interface is the way you will go about starting, stopping, and controlling the underlying ROS software. For more advanced users these tools will allow you to study a ROS system by exploring the underlying software processes in the system.

There are only two things you need to memorize from this section. The first command simply tells your computer that you are using ROS, and what version of ROS you want to use. Let's take a look at the magic command:

source /opt/ros/eloquent/setup.bash

If everything is working correctly, this command should simply return. Nothing happens that you can see, but underneath the hood you've just told this particular shell that you are using ROS 2 Eloquent Elusor, and where all the ROS programs and files live. You should plan on doing this every time you want to use ROS. The most common mistake new users have is not running this command. If you're not sure if you ran the command in a shell, that's okay. The command is idempotent; running it twice in a row won't break anything. You can run it a million times in a row and it won't make any difference.

The other command you need to commit to memory is ros2. Almost everything in

the ROS 2 CLI starts with ros2. Go ahead and try it in the same shell where you just sourced the setup file.

If everything is working correctly you should see the following:

$ ros2

usage: ros2 [-h] Call `ros2 <command> -h` for more detailed usage. ...

ros2 is an extensible command-line tool for ROS 2.

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

Commands:

action Various action related sub-commands

component Various component related sub-commands

daemon Various daemon related sub-commands

doctor Check ROS setup and other potential issues

interface Show information about ROS interfaces

launch Run a launch file

lifecycle Various lifecycle related sub-commands

msg Various msg related sub-commands

multicast Various multicast related sub-commands

node Various node related sub-commands

param Various param related sub-commands

pkg Various package related sub-commands

run Run a package specific executable

security Various security related sub-commands

service Various service related sub-commands

srv Various srv related sub-commands

topic Various topic related sub-commands

wtf Use `wtf` as alias to `doctor`

Call `ros2 <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

From this one command you can figure out what every single ROS 2 CLI program does and

how to use it. The ROS 2 CLI has a syntax just like most languages. All ROS CLI commands start

with ros2, followed by a command. After the command any number of other things

can come; you can append --help or -h to see the documentation and find out what arguments any of the commands are expecting.

The rest of this section just walks through each of the commands one by one.

Writing commands using the command line is tricky and error

prone. There are a couple of tools you can use to make the process much

smoother. The first is the TAB key, which attempts to auto complete whatever you type.

It can't read your mind, but for common command combinations you usually only need to type the

first one or two letters. Another tool is the up arrow key. When you use the

command line sometimes you mistype a command, or need to rerun a

command. Pressing the up key will cycle through the previous commands which you

can modify and rerun as needed.

Running Your First ROS Program

Let's get started with our first ROS CLI command. The first command we'll visit

is run. Let's start by looking at the documentation for the run command:

$ ros2 run

usage: ros2 run [-h] [--prefix PREFIX] package_name executable_name ...

ros2 run: error: the following arguments are required: package_name, executable_name, argv

To get more complete information about a ROS 2 command, simply ask the command for help by

adding --help to the command. Let's try that again:

$ ros2 run --help

usage: ros2 run [-h] [--prefix PREFIX] package_name executable_name ...

Run a package specific executable

positional arguments:

package_name Name of the ROS package

executable_name Name of the executable

argv Pass arbitrary arguments to the executable

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--prefix PREFIX Prefix command, which should go before the executable.

Command must be wrapped in quotes if it contains spaces

(e.g. --prefix 'gdb -ex run --args').

We can see that ros2 run is the

command to, "Run a package specific executable." In ROS 2 collections of ROS

software are gathered into logical units called packages. Each package

contains all of the source code for the package as a variety of other data that

tells ROS how to build and compile the package and the names of all the

programs, also called executables, that can be found in the package. The line

below the description then gives the positional arguments for the

package. Positional arguments are the words and values that come after ros2

and the command you run. In this case the syntax for the command sentence we

want to write is as follows:

ros2 run <package name> <program/executable name> <args>

There is one piece of missing information here. What is this argv that the

command is asking for? The argv element is programmer short hand for variable

arguments, and it simply means, "some number of additional arguments that are

determined by the executable". It is worth noting that a program can have zero

arguments and you can just leave it blank. This is actually how a lot of

programs work. For example, say we had a package

called math, and an executable called add that takes in two numbers and

returns the result. In this case argv would be the two numbers to add. The

final command would look like:

ros2 run math add 1 2

Finally, below the positional arguments we have optional arguments. You don't need to included them, unless you need to.

Now that we've looked into our help file let's run our first ROS program. For

these tutorials we're going to use a package called turtlesim, and the program

we want to run is turtlesim_node. Let's run this program (remember your tab

complete!). Your command should look like the following:

ros2 run turtlesim turtlesim_node

If everything goes smoothly you should see the following:

[INFO] [turtlesim]: Starting turtlesim with node name /turtlesim

[INFO] [turtlesim]: Spawning turtle [turtle1] at x=[5.544445], y=[5.544445], theta=[0.000000]

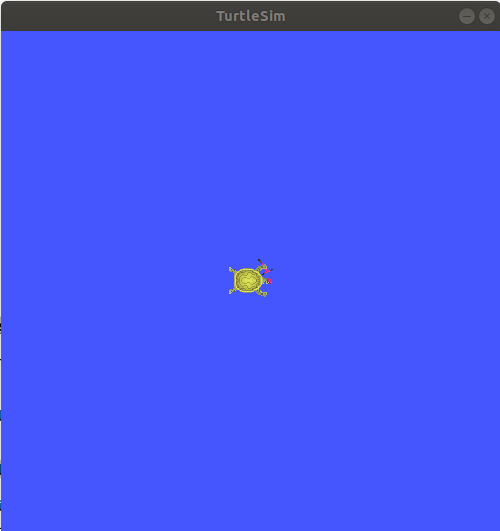

A window should also pop up with a cute little turtle that looks like the one below:

The real power in ROS isn't that it can run a program, it is that it can run lots of programs all at the same time, all talking together to control a robot, or multiple robots, all working together. To illustrate this let's run a second ROS program that makes our little turtle move around.

To do this we'll first open a new terminal (using CTRL-SHIFT-T). Next we'll

tell that terminal that we want to use ROS Eloquent by using the source command.

Finally, we'll run another program in the

turtlesim package to draw a square. See if you can find the program

yourself (hint: use TAB). If everything works you should have typed the following, and the

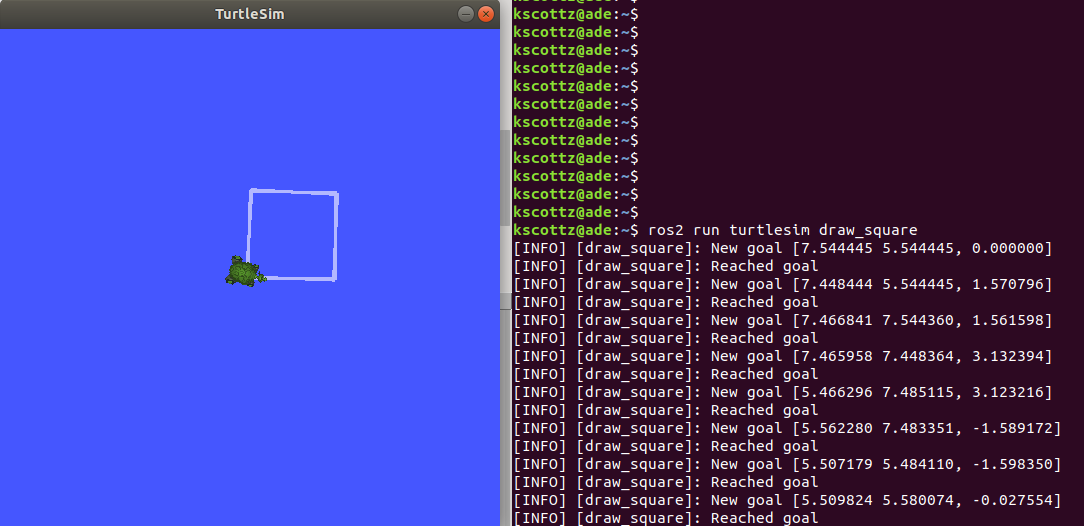

following output should be visible:

$ source /opt/ros/eloquent/setup.bash

$ ros2 run turtlesim draw_square

[INFO] [draw_square]: New goal [7.544445 5.544445, 0.000000]

[INFO] [draw_square]: Reached goal

[INFO] [draw_square]: New goal [7.448444 5.544445, 1.570796]

[INFO] [draw_square]: Reached goal

Your screen should look roughly like this:

It is worth noting that you can stop any ROS program by pressing the Ctrl and

C keys at the same time in the terminal; we call this CTRL-C (note that

CTRL-SHIFT-C and CTRL-SHIFT-V are responsible for copy and paste in a Linux terminal).

Feel free to try it out. Start and stop the programs, and then

restart them before moving on.

ROS Topics

We now have two ROS 2 programs running from the turtlesim package.

There is turtle_node that opens our turtle simulation, and draw_square

that makes the turtle in turtle_node move around. How are these two

programs communicating?

ROS programs, also called nodes, communicate over topics on the ROS message bus. ROS topics use namespaces to distinguish themselves. For example, in a vehicle running ROS, the positions of each wheel may be organized as follows:

/wheels/front/driver/velocity

/wheels/front/passenger/velocity

/wheels/rear/driver/velocity

/wheels/rear/passenger/velocity

The key thing to realize about topics is that the data they contain is dynamic, meaning it changes

constantly. In our vehicle example the velocity of each wheel might be measured

one thousand times a second or more. Since the data in a ROS topic is constantly

changing, an important distinction for a topic is whether the topic is "creating"

or as we like to say in ROS publishing, or if it is reading the data, what we call

subscribing to the topic. Many ROS nodes subscribe to one set of topics,

process that input data, and then publish to another set of topics.

Let's return to our turtlesim example and see if we can use the ROS CLI to

understand the topics, publishers, and subscribers.

To see sub commands and syntax for the topic command, we'll run: ros2 topic --help.

This command outputs the following:

$ ros2 topic --help

usage: ros2 topic [-h] [--include-hidden-topics]

Call `ros2 topic <command> -h` for more detailed usage. ...

Various topic related sub-commands

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--include-hidden-topics

Consider hidden topics as well

Commands:

bw Display bandwidth used by topic

delay Display delay of topic from timestamp in header

echo Output messages from a topic

find Output a list of available topics of a given type

hz Print the average publishing rate to screen

info Print information about a topic

list Output a list of available topics

pub Publish a message to a topic

type Print a topic's type

Call `ros2 topic <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

There are quite a

few sub commands; we won't discuss all of them, but let's look closely at a few.

Sub commands have their

own help command. Why don't we examine the list command. Repeating our command

pattern let's try running ros2 topic list --help.

usage: ros2 topic list [-h] [--spin-time SPIN_TIME] [-t] [-c]

[--include-hidden-topics]

Output a list of available topics

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--spin-time SPIN_TIME

Spin time in seconds to wait for discovery (only

applies when not using an already running daemon)

-t, --show-types Additionally show the topic type

-c, --count-topics Only display the number of topics discovered

--include-hidden-topics

Consider hidden topics as well

As indicated at the top of this command help file, ros2 topic list will

"Output a list of available topics." There appears to be a variety of

optional arguments that we don't need to include if we don't want to. However,

the -t, --show-types line looks interesting. It is worth noting that command

arguments, sometimes called flags, can have two types. A short form indicated

with a single dash ("-"), and a long form indicated by a double dash

("--"). Don't worry, despite looking different both versions of the argument do

the same thing. Let's try running this command, sub command pair with the

-show-types argument.

$ ros2 topic list --show-types

/parameter_events [rcl_interfaces/msg/ParameterEvent]

/rosout [rcl_interfaces/msg/Log]

/turtle1/cmd_vel [geometry_msgs/msg/Twist]

/turtle1/color_sensor [turtlesim/msg/Color]

/turtle1/pose [turtlesim/msg/Pose]

On the left hand side we see all of the ROS topics

running on the system, each starting with /. We can see that most of them are gathered in the

/turtle1/ group. This group defines all the inputs and outputs of the little

turtle on our screen. The words in brackets ([]) to the right of the topic

names define the messages used on the topic. Our car wheel example was

simple, we were only publishing velocity, but ROS allows you to publish more

complex data structures that are defined by a message type. When we added the

--show-types flag we told the command to include this information. We'll dig

into messages in detail a bit later.

One of the more commonly used topic sub commands is

info. Unsurprisingly, info provides info about a topic. Let's peek at its

help file using ros2 topic info --help

$ ros2 topic info --help

usage: ros2 topic info [-h] topic_name

Print information about a topic

positional arguments:

topic_name Name of the ROS topic to get info (e.g. '/chatter')

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

That seems pretty straight forward. Let's give it a go by running it on

/turtle1/pose

$ ros2 topic info /turtle1/pose

Type: turtlesim/msg/Pose

Publisher count: 1

Subscriber count: 1

What does this command tell us? First it tells us the message type for the

/turtle1/pose topic, which is /turtlesim/msg/Pose. From this we can determine that the

message type comes from the turtlesim package, and its type is Pose. ROS

messages have a predefined message type that can be shared by different

programming languages and between different nodes. We can also see that this

topic has a single publisher, that is to say a single node generating data on the

topic. The topic also has a single subscriber, also called a listener, who is

processing the incoming pose data.

If we only wanted to know the message type of a topic

there is a sub command just for that called, type. Let's take a look at its

help file and its result:

$ ros2 topic type --help

usage: ros2 topic type [-h] topic_name

Print a topic's type

positional arguments:

topic_name Name of the ROS topic to get type (e.g. '/chatter')

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

kscottz@kscottz-ratnest:~/Code/ros2multirobotbook$ ros2 topic type /turtle1/pose

turtlesim/msg/Pose

While it is not part of the topic command it is worthwhile for us to jump ahead

briefly and look at one particular command, sub command pair, namely the interface

command and the show sub command. This sub command will print all the

information related to a message type so you can better understand the data

being moved over a topic. In the previous example we saw that the topic type

sub command told us the /turtle1/pose topic has a type turtlesim/msg/Pose.

But what does turtlesim/msg/Pose data look like? We can look at the data

structure transferred by this topic by running the ros2 interface show

sub command and giving the message type name as an input. Let's look at the help

for this sub command and its output:

$ ros2 interface show --help

usage: ros2 interface show [-h] type

Output the interface definition

positional arguments:

type Show an interface definition (e.g. "std_msgs/msg/String")

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

$ ros2 interface show turtlesim/msg/Pose

float32 x

float32 y

float32 theta

float32 linear_velocity

float32 angular_velocity

We can see the values x and y which are the position coordinates of our turtle,

and that they are of type float32.

theta is the direction the head is pointing. The

next two values, linear_velocity and angular_velocity, are how

fast the turtle is moving and how quickly it is turning, respectively. To summarize, this

message tells us where a turtle is on the screen, where it is headed, and how

fast it is moving or rotating.

Now that we know what ROS topics are on our simple turtlesim, and their message

types, we can dig in and find out more about how everything works. If we look

back at our topic sub commands, we can see a sub command called echo. Echo is

computer jargon that means "repeat" something. If you echo a topic it means you

want the CLI to repeat what's on a topic. Let's look at the echo sub command's

help text:

$ ros2 topic echo --help

usage: ros2 topic echo [-h]

[--qos-profile {system_default,sensor_data,services_default,parameters,parameter_events,action_status_default}]

[--qos-reliability {system_default,reliable,best_effort}]

[--qos-durability {system_default,transient_local,volatile}]

[--csv] [--full-length]

[--truncate-length TRUNCATE_LENGTH] [--no-arr]

[--no-str]

topic_name [message_type]

Output messages from a topic

positional arguments:

topic_name Name of the ROS topic to listen to (e.g. '/chatter')

message_type Type of the ROS message (e.g. 'std_msgs/String')

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--qos-profile {system_default,sensor_data,services_default,parameters,parameter_events,action_status_default}

Quality of service preset profile to subscribe with

(default: sensor_data)

--qos-reliability {system_default,reliable,best_effort}

Quality of service reliability setting to subscribe

with (overrides reliability value of --qos-profile

option, default: best_effort)

--qos-durability {system_default,transient_local,volatile}

Quality of service durability setting to subscribe

with (overrides durability value of --qos-profile

option, default: volatile)

--csv Output all recursive fields separated by commas (e.g.

for plotting)

--full-length, -f Output all elements for arrays, bytes, and string with

a length > '--truncate-length', by default they are

truncated after '--truncate-length' elements with

'...''

--truncate-length TRUNCATE_LENGTH, -l TRUNCATE_LENGTH

The length to truncate arrays, bytes, and string to

(default: 128)

--no-arr Don't print array fields of messages

--no-str Don't print string fields of messages

Wow, that's a lot of features. The top of the help files says that this CLI

program "output[s] messages from a topic." As we scan the positional arguments we see one

required argument, a topic name, and an optional message type. We know the

message type is optional because it has square brackets ([]) around it. Let's

give the simple case a whirl before we address some of the optional

elements. Two things to keep in mind: first is that topics are long and easy to mess

up, so use the TAB key. Second is that this will print a lot of data, fast. You can

use CTRL-C to stop the command and stop all the output. Let's take a look at the

/turtle1/pose topic.

$ ros2 topic echo /turtle1/pose

x: 5.4078755378723145

y: 7.081490516662598

theta: -1.0670461654663086

linear_velocity: 1.0

angular_velocity: 0.0

---

x: 5.4155988693237305

y: 7.067478179931641

theta: -1.0670461654663086

linear_velocity: 1.0

angular_velocity: 0.0

---

x: 5.423322677612305

y: 7.053465843200684

theta: -1.0670461654663086

linear_velocity: 1.0

angular_velocity: 0.0

---

<<GOING ON FOREVER>>

Let's examine what is going on. Between the

dashes (---) is a single ROS message on our topic. If you examine the numbers

closely you can see that they are changing, and doing so in relation to the

movement of the turtle. Going back to our car example you can see how this would

be useful for understanding the instantaneous velocity of each of our wheels.

Now that we have the basics down let's dig into a few of the optional

arguments. We see a variety of commands that start with --qos. "QOS" here

means "quality of service" and it is a really cool feature that is only in

ROS 2. Without getting too technical, QOS is a way of asking for a certain level

of networking robustness. A ROS system can operate over a network, and just like

streaming video or video games, packets can get dropped or not get to their

destination. The OS settings help you control which packets are the most

important and should get the highest priority.

Most of the other commands deal with changing the output format of this CLI

program, but there is one in particular that is super handy, and it is also new

in ROS 2. The --csv flag stands for "comma separated values" and it a very

simple way of defining a spreadsheet. What this argument does is make the topic

echo command output data in the comma separate value format. Many command lines

allow you send data from the screen to a file, saving the data for later

review or analysis. To do this file saving in Linux we use the > character

followed by a file name. Below are two examples of using the --csv argument:

$ ros2 topic echo /turtle1/pose --csv

7.097168922424316,8.498645782470703,2.442624092102051,0.0,0.4000000059604645

7.097168922424316,8.498645782470703,2.449024200439453,0.0,0.4000000059604645

...

<<CTRL-C>>

$ ros2 topic echo /turtle1/pose --csv > mydata.csv

<<nothing happens>>

<<CTRL-C>>

The second command above creates a file called mydata.csv. You can look at it

using a CLI utility called less (press q to quit), or open it with your

favorite spreadsheet tool.

Now that we've looked at ros2 topic echo let's take a look at a few other

topic sub commands. One thing you may have noticed is that topics can output a lot

of data! More complex robots, like a self driving car, can saturate a high

speed internet connection with how much data it produces. There are two topic

sub commands that can be used to diagnose performance issues. The first

sub command is topic hz which is the abbreviation of Hertz, the unit of

frequency. The Hz sub command will

tell you how often a particular topic produces a message. Similarly there is

the topic bw sub command, where bw stands for bandwidth, which is a

engineering term related to the volume of data being produced. A high

bandwidth connection can move more data, like high definition video, than a low

bandwidth data, which might move a radio show. Let's take a look at the help

for these two commands:

$ ros2 topic hz --help

usage: ros2 topic hz [-h] [--window WINDOW] [--filter EXPR] [--wall-time]

topic_name

Print the average publishing rate to screen

positional arguments:

topic_name Name of the ROS topic to listen to (e.g. '/chatter')

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--window WINDOW, -w WINDOW

window size, in # of messages, for calculating rate

(default: 10000)

--filter EXPR only measure messages matching the specified Python

expression

--wall-time calculates rate using wall time which can be helpful

when clock is not published during simulation

$ ros2 topic bw --help

usage: ros2 topic bw [-h] [--window WINDOW] topic

Display bandwidth used by topic

positional arguments:

topic Topic name to monitor for bandwidth utilization

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--window WINDOW, -w WINDOW

window size, in # of messages, for calculating rate

(default: 100)

Both bw and hz follow the same pattern, they simply take in a topic name

followed by a few optional arguments. The only argument worth noting is the

window argument. Both of these commands calculate statistics for a series of

messages; how many messages to use in calculating those statistics is the window

size. The default value for window is 100, so when you call ros2 topic bw it

will first collect 100 messages then use that data to calculate the average

message size. Let's give it a shot (use TAB to complete and CTRL-C to exit).

$ ros2 topic hz /turtle1/pose

average rate: 60.021

min: 0.001s max: 0.073s std dev: 0.00731s window: 65

average rate: 61.235

min: 0.001s max: 0.073s std dev: 0.00523s window: 128

$ ros2 topic bw /turtle1/pose

Subscribed to [/turtle1/pose]

average: 1.44KB/s

mean: 0.02KB/s min: 0.02KB/s max: 0.02KB/s window: 46

average: 1.52KB/s

mean: 0.02KB/s min: 0.02KB/s max: 0.02KB/s window: 100

As we can see above, the hz command says that the topic is publishing messages

at 60.021, where the unit is hz, or 60.021 times a second. Notice that the

command gives the publishing frequency as an average, followed by the minimum,

maximum, and standard deviation, in seconds. The bandwidth sub command is very

similar; and we can see that the topic is producing 1.44 kilobytes of data per

second. This command has similar outputs around the minimum, maximum, and mean.

One tool that is handy when exploring topics is understanding their type. While

we have already looked at the interface command to see what integral types make up

a topic, the topic command has both a tool to query the type of a topic, and a

means to search all topics for a specific type. If all you want to know is a

topic's type you can use the type command which will return a type that can

then be further explored with the interface command. If instead you would like

to know what topics use a particular message type you can use the topic find

command, sub command pair. Both the topic type and topic interface command,

sub command pairs have a very limited set of optional arguments, so we simply

provide them with our desired topic or message type. Let's take a look at these two commands together:

$ ros2 topic type --help

usage: ros2 topic type [-h] topic_name

Print a topic's type

positional arguments:

topic_name Name of the ROS topic to get type (e.g. '/chatter')

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

$ ros2 topic type /turtle1/pose

turtlesim/msg/Pose

$ ros2 topic find --help

usage: ros2 topic find [-h] [-c] [--include-hidden-topics] topic_type

Output a list of available topics of a given type

positional arguments:

topic_type Name of the ROS topic type to filter for (e.g.

'std_msg/msg/String')

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-c, --count-topics Only display the number of topics discovered

--include-hidden-topics

Consider hidden topics as wel

$ ros2 topic find turtlesim/msg/Pose

/turtle1/pose

The last sub command for the topic command is pub, which simply means publish.

It allows you to publish a command to any ROS topic from the command

line. While you shouldn't need to use this command regularly it can be

particularly handy for testing and debugging when you are building a robot

system. The pub command has a number of optional arguments that allow you to

send one or more messages, and with different quality of service (QoS)

presets. The format of the command is ros2 topic pub TOPIC_NAME MESSAGE_TYPE VALUES, which means for it to work successfully you must include a

target topic, the topic's message type, and finally the message's values. The

values for the message are specified in the YAML format and we can use the

interface show command to understand the format. To illustrate the utility of this

command we'll issue a message to rotate and stop our turtle by publishing

to the /turtle1/cmd_vel/ topic. Let's first take a look at the topic pub

documentation before we construct our command:

$ ros2 topic pub --help

usage: ros2 topic pub [-h] [-r N] [-p N] [-1] [-n NODE_NAME]

[--qos-profile {system_default,sensor_data,services_default,parameters,parameter_events,action_status_default}]

[--qos-reliability {system_default,reliable,best_effort}]

[--qos-durability {system_default,transient_local,volatile}]

topic_name message_type [values]

Publish a message to a topic

positional arguments:

topic_name Name of the ROS topic to publish to (e.g. '/chatter')

message_type Type of the ROS message (e.g. 'std_msgs/String')

values Values to fill the message with in YAML format (e.g.

"data: Hello World"), otherwise the message will be

published with default values

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-r N, --rate N Publishing rate in Hz (default: 1)

-p N, --print N Only print every N-th published message (default: 1)

-1, --once Publish one message and exit

-n NODE_NAME, --node-name NODE_NAME

Name of the created publishing node

--qos-profile {system_default,sensor_data,services_default,parameters,parameter_events,action_status_default}

Quality of service preset profile to publish with

(default: system_default)

--qos-reliability {system_default,reliable,best_effort}

Quality of service reliability setting to publish with

(overrides reliability value of --qos-profile option,

default: system_default)

--qos-durability {system_default,transient_local,volatile}

Quality of service durability setting to publish with

(overrides durability value of --qos-profile option,

default: system_default)

Since we want to manually move our turtle we will use the --once

flag to issue our command once. It is worth noting that the message type used to

command the velocity of the turtle is complex in that it is made up of other

message types so we'll have to query the base message type. Here's a rough summary of what we will do:

- Print the

cmd_veltopic type usingros2 topic type, which isgeometry_msgs/msg/Twist - Determine the structure of the

Twistmessage type usinginterface show. - Determine the structure of the

Vector3, which is part of theTwistmessage type usinginteface showcommand a second time. - Create the YAML syntax for our command. Note the YAML syntax below as it is

rather tricky! The YAML is wrapped in single quotes and a top level set of

curly braces, while subsequent levels follow the

pattern of

name:value, andname:{name1:val1,name2:val2}for nested types like theTwistcommand. - Issue the command using

ros2 pub.

$ ros2 topic type /turtle1/cmd_vel

geometry_msgs/msg/Twist

$ ros2 interface show geometry_msgs/msg/Twist

# This expresses velocity in free space broken into its linear and angular parts.

Vector3 linear

Vector3 angular

$ ros2 interface show geometry_msgs/msg/Vector3

# This represents a vector in free space.

float64 x

float64 y

float64 z

$ ros2 topic pub --once /turtle1/cmd_vel geometry_msgs/msg/Twist '{linear: {x: 4.0,y: 4.0, z: 0.0}, angular: {x: 0.0, y: 0.0, z: 0.0}}'

If you did everything correctly you should have moved around the turtle on the screen. Try changing the command to draw a small picture.

ROS 2 Services and Actions

As discussed previously, services are the name given to short, synchronous robot behaviors that can be done quickly, like turning on lights and switching components on or off. Actions are longer term, asynchronous, tasks that may have intermediate steps. A classic example of an action is navigation: a robot is provided a goal position and asked to navigate to that goal. Try as the robot might, since it cannot move infinitely fast, it takes time to move to a goal and sometimes its path may become blocked.

These two primitives are the backbone of most robotic systems using ROS, and learning

how to use them via the command line will allow you quickly and easily command

a robot to complete a task for you. To aid in clarity of this section we'll

also touch on the ros2 node command to determine what node, or software

process, is conducting a particular action or service.

Let's get nodes out of the way quickly. ROS nodes are

small programs, running in their own process. A ROS system can have ten,

hundreds, or even thousands of nodes running concurrently. Moreover, a ROS

system can have multiple copies of the same node running concurrently on the

same system. In the case of our turtle simulation we can actually create

multiple turtles, each with their own node, all running the exact same

program. ROS Nodes, like ROS topics, have namespaces so that you can address

specific nodes in the case where multiple copies of the same node (program) are

running. Let's dig in a bit by restarting our turtle simulation in a terminal

using ros2 run turtlesim turtlesim_node. Now in a new terminal let's first

examine what ros2 node has to offer by asking for help.

$ ros2 node --help

usage: ros2 node [-h]

Call `ros2 node <command> -h` for more detailed usage. ...

Various node related sub-commands

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

Commands:

info Output information about a node

list Output a list of available nodes

Call `ros2 node <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

Much like topics, we see two sub commands, info and list. node list works much the

same as topic list and simply prints a list of all running nodes. Let's see what

is running on our system:

$ ros2 node list

/turtlesim

We have a single node running called "turtlesim". node info works in a way

very similar to topic info except that it lists information about the nodes we

give it. Let's call it with our single ROS Node /turtlesim as its

argument:

$ ros2 node info /turtlesim

/turtlesim

Subscribers:

/parameter_events: rcl_interfaces/msg/ParameterEvent

/turtle1/cmd_vel: geometry_msgs/msg/Twist

Publishers:

/parameter_events: rcl_interfaces/msg/ParameterEvent

/rosout: rcl_interfaces/msg/Log

/turtle1/color_sensor: turtlesim/msg/Color

/turtle1/pose: turtlesim/msg/Pose

Service Servers:

/clear: std_srvs/srv/Empty

/kill: turtlesim/srv/Kill

/reset: std_srvs/srv/Empty

/spawn: turtlesim/srv/Spawn

/turtle1/set_pen: turtlesim/srv/SetPen

/turtle1/teleport_absolute: turtlesim/srv/TeleportAbsolute

/turtle1/teleport_relative: turtlesim/srv/TeleportRelative

/turtlesim/describe_parameters: rcl_interfaces/srv/DescribeParameters

/turtlesim/get_parameter_types: rcl_interfaces/srv/GetParameterTypes

/turtlesim/get_parameters: rcl_interfaces/srv/GetParameters

/turtlesim/list_parameters: rcl_interfaces/srv/ListParameters

/turtlesim/set_parameters: rcl_interfaces/srv/SetParameters

/turtlesim/set_parameters_atomically: rcl_interfaces/srv/SetParametersAtomically

Service Clients:

Action Servers:

/turtle1/rotate_absolute: turtlesim/action/RotateAbsolute

Action Clients:

Wow, that's a lot of information, some of which looks familiar. We can see all the topics that the node subscribes to, as well as all the nodes it publishes to. We can also see a number of "action servers" and "service servers". It is worth noting the client and server relationship here. Since ROS may have multiple nodes running some nodes may offer services (these are servers), and other ROS nodes may call those servers (these are the clients). The clients can be other ROS nodes, or for these examples, a human using the CLI.

The command line interface for services and actions are very similar, in fact

they both have only four sub commands. Let's run the action and service

commands and compare them:

$ ros2 action --help

usage: ros2 action [-h]

Call `ros2 action <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

...

Various action related sub-commands

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

Commands:

info Print information about an action

list Output a list of action names

send_goal Send an action goal

show Output the action definition

Call `ros2 action <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

$ ros2 service --help

usage: ros2 service [-h] [--include-hidden-services]

Call `ros2 service <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

...

Various service related sub-commands

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--include-hidden-services

Consider hidden services as well

Commands:

call Call a service

find Output a list of available services of a given type

list Output a list of available services

type Output a service's type

Call `ros2 service <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

We can see that both commands have a list command that gives a list of

available services or actions. If we had multiple nodes running and wanted to

see every service offered, calling ros2 node info on each node would be very

inefficient, particularly if we had tens, or even hundreds of nodes running.

In this case it would be much more efficient to use the list commands for the

action and service commands. We can run these commands below and see that we get

roughly the same list of actions and services listed in our single nodes:

$ ros2 service list

/clear

/kill

/reset

/spawn

/turtle1/set_pen

/turtle1/teleport_absolute

/turtle1/teleport_relative

/turtlesim/describe_parameters

/turtlesim/get_parameter_types

/turtlesim/get_parameters

/turtlesim/list_parameters

/turtlesim/set_parameters

/turtlesim/set_parameters_atomically

kscottz@kscottz-ratnest:~$ ros2 action list

/turtle1/rotate_absolute

Let's begin digging into services. There seem to be quite a few services

listed. Let's take a look at the /spawn service, which will create more

turtles. ROS services and actions use messages similar to those used in topics

to communicate. In fact, actions and services are built on top of messages.

We can use the service type sub command to determine the message type

used by a particular service. We can find specifics of the message by using the

interface show command. Let's see this in practice with the spawn service:

$ ros2 service type /spawn

turtlesim/srv/Spawn

$ ros2 interface show turtlesim/srv/Spawn

float32 x

float32 y

float32 theta

string name # Optional. A unique name will be created and returned if this is empty

---

string name

We can see from the output above that the spawn message takes three float32

values for its position and orientation as well a string for its name. The

--- indicate the return value of the services. Unlike topics, services have

a return value, which enables them to do things like perform computations and

calculations.

Let's examine the help for calling a service by running ros2 service call --help:

$ ros2 service call --help

usage: ros2 service call [-h] [-r N] service_name service_type [values]

Call a service

positional arguments:

service_name Name of the ROS service to call to (e.g. '/add_two_ints')

service_type Type of the ROS service (e.g. 'std_srvs/srv/Empty')

values Values to fill the service request with in YAML format (e.g.

"{a: 1, b: 2}"), otherwise the service request will be

published with default values

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-r N, --rate N Repeat the call at a specific rate in Hz

The syntax here is very similar to publishing to a topic, but instead of using a

a topic name we use a service name. The service type is just like the topic type

that we used in the past, but instead of using a message type we need a service

type. Finally we give it a value in YAML format. A YAML string must be encased

in single quotes. Let's try calling a service by creating a turtle

named Larry at a position where all values are zero (use TAB complete).

$ ros2 service call /spawn turtlesim/srv/Spawn "{x: 0, y: 0, theta: 0.0, name: 'Larry'}"

requester: making request: turtlesim.srv.Spawn_Request(x=0.0, y=0.0, theta=0.0, name='Larry')

response:

turtlesim.srv.Spawn_Response(name='Larry')

If everything is working correctly you should now have a turtle named "Larry" in the lower left hand corner of the screen:

Try exploring the other services offered, or creating more turtles at different locations and moving them around.

Let's move on to actions. As mentioned previously, actions differ from services in a few ways and offer a number of advantages. Actions have the following advantages:

- Actions have a

goal. That is to say you send them a goal, and they attempt to complete it. - Actions can reject goal requests. This prevents them from becoming too busy.

- Actions are asynchronous and can perform tasks "while you wait."

- Actions will provide you with "updates" with information about their progress while you wait.

- Actions are preemptable, meaning you can cancel them if you change your mind.

Just like with services, we'll first figure out how to call the sole action in

our ROS system by using the action list, action show, and action info

commands. Recall, that when we called ros2 action list we got a single

service. Now that we have Larry things have changed. Let's take a look:

$ ros2 action list

/Larry/rotate_absolute

/turtle1/rotate_absolute

Now there are two actions available, one for Larry and one for turtle1.

Let's rotate turtle1 to face Larry. First we'll call action info

using /turtle1/rotate_absolute as the input and see what we get:

$ ros2 action info /turtle1/rotate_absolute

Action: /turtle1/rotate_absolute

Action clients: 0

Action servers: 1

/turtlesim

Well, that tells us about the client and servers, but it really isn't

helpful for our goal of moving Larry. Why don't we look at the action send_goal help and see if we can

figure out how to use it:

$ ros2 action send_goal --help

usage: ros2 action send_goal [-h] [-f] action_name action_type goal

Send an action goal

positional arguments:

action_name Name of the ROS action (e.g. '/fibonacci')

action_type Type of the ROS action (e.g.

'example_interfaces/action/Fibonacci')

goal Goal request values in YAML format (e.g. '{order: 10}')

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-f, --feedback Echo feedback messages for the goal

This command needs an action name, an action type, and a goal in YAML. We know the action name, and we know how to write YAML, so all we need is to determine the action type. The best way to get the action type is the same way we published a message.

We see each of our turtles have one service called rotate_absolute.

Let's dig into this action using the info sub command. This command has a -t

flag to list the types of messages.

$ ros2 action info /turtle1/rotate_absolute -t

Action: /turtle1/rotate_absolute

Action clients: 0

Action servers: 1

/turtlesim [turtlesim/action/RotateAbsolute]

The first line lists the action

name. The second line gives the current number of clients for the

action. The Action servers line gives the total number of action

servers for this action. The last line gives the package and message

type for the action.

We can see here that we need to know the action name, the type, and the values. Now the only problem is figuring out the format of the action type.

Let's understand the RotateAbsolute action message

The ros2 interface show command can be used to find the type of action

message. Let's take a look:

$ ros2 interface show turtlesim/action/RotateAbsolute

# The desired heading in radians

float32 theta #< --- This section is the GOAL

---

# The angular displacement in radians to the starting position

float32 delta #< --- This section is the final result, different from the goal.

---

# The remaining rotation in radians

float32 remaining # < --- This is the current state.

What does this say about rotate absolute?

- There is a float input,

theta, the desired heading. This first section is the actual goal. deltais the angle from the initial heading. This is the value returned when the action completes.remainingis the remaining radians to move. This is the value posted by the action while the action is being done.

With this information we can create our call to the action server. We'll

use the -f flag to make this a bit clearer. Keep an eye on your turtle! It should move, slowly.

$ ros2 action send_goal -f /turtle1/rotate_absolute turtlesim/action/RotateAbsolute {'theta: 1.70'}

Waiting for an action server to become available...

Sending goal:

theta: 1.7

Feedback:

remaining: 0.11599969863891602

Goal accepted with ID: 35c40e91590047099ae5bcc3c5151121

Feedback:

remaining: 0.09999966621398926

Feedback:

remaining: 0.06799960136413574

Feedback:

remaining: 0.03599953651428223

Result:

delta: -0.09600019454956055

Goal finished with status: SUCCEEDED

If everything worked correctly we should see our turtle has rotated.

ROS Parameters

In ROS, parameters are values that are shared between nodes in the system (if you are familiar with the blackboard design pattern in software engineering). Parameters are values that any node can query or write to. Another good analogy would be global constants in normal software programs. Parameters are best used to configure your robot. For example, if you were building an autonomous vehicle and wanted to cap the maximum velocity of the vehicle at 100 km/h, you could create a parameter called "MAX_SPEED" that is visible to all the nodes.

Let's take a look at the param command by running ros2 param --help.

$ ros2 param --help

Various param related sub-commands

Commands:

delete Delete parameter

get Get parameter

list Output a list of available parameters

set Set parameter

Call `ros2 param <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

At a high level, ROS 2's param command has sub commands to get and set a variable,

along with a list functionality, and a delete command. As with most of the

other commands we've worked through, it is instructive to look at list

first. Let's see what the docs say about the list command and then see what

happens when we call the sub command:

$ ros2 param list --help

usage: ros2 param list [-h] [--spin-time SPIN_TIME] [--include-hidden-nodes]

[--param-prefixes PARAM_PREFIXES [PARAM_PREFIXES ...]]

[node_name]

Output a list of available parameters

positional arguments:

node_name Name of the ROS node

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--spin-time SPIN_TIME

Spin time in seconds to wait for discovery (only

applies when not using an already running daemon)

--include-hidden-nodes

Consider hidden nodes as well

--param-prefixes PARAM_PREFIXES [PARAM_PREFIXES ...]

Only list parameters with the provided prefixes

$ ros2 param list

/turtlesim:

background_b

background_g

background_r

use_sim_time

The only argument of note in this sub command is the node_name which allows

you to narrow the scope of param list to only those parameters used by a particular

node. In terms of parameters in the turtlesim node, we see that our call to param list gives us: three background color control params named

background_x and a use_sim_time parameter. To learn all about the param

command why don't we try to change these background color parameters using the

CLI.

The first step in changing the background color is to see what the current color

is. The param get sub command requires both a node name and a parameter

name. In our list above we can see the node name as the top level element with

the forward slash in front of it, namely /turtlesim. The syntax for param get is ros2 param get <node_name> <param>. Let's give it a whirl and see our

current background color values.

$ ros2 param get /turtlesim background_b

Integer value is: 255

$ ros2 param get /turtlesim background_g

Integer value is: 86

$ ros2 param get /turtlesim background_r

Integer value is: 69

On most computers color is represented as a triplet of <R,G,B> values. The color value of <69,86,255> corresponds to a periwinkle blue color. To change the color of the turtlesim we need to first set the parameter value and then reset the turtlesim to make it apply the color changes. We covered the basics of calling a service previously so we won't cover the steps of constructing a service call. Let's try setting our background color's blue component to 128.

$ ros2 param set turtlesim background_b 128

Set parameter successful

$ ros2 service call /reset std_srvs/srv/Empty

requester: making request: std_srvs.srv.Empty_Request()

response:

std_srvs.srv.Empty_Response()

If everything worked correctly your turtle should look like the screen below.

ROS Bags

ROS bags are ROS's tool for recording, and replaying data. ROS bags are like log files that let you store data along with messages. ROS systems can generate a lot of data, so when you bag data you must select which topics you want. Bags are a great tool for testing and debugging your application and a great tool for building robust unit tests.

Let's take a look at the root ROS Bag command by typing ros2 bag --help into

the terminal. If you get an error you might need to install ROS Bag as it is

often in a separate package. On Linux you can run sudo apt install ros-eloquent-ros2bag and it should automatically install the package for you.

$ ros2 bag -h

usage: ros2 bag [-h] Call `ros2 bag <command> -h` for more detailed usage. ...

Various rosbag related sub-commands

Commands:

info ros2 bag info

play ros2 bag play

record ros2 bag record

As you can see there are three sub commands, record, play, and info. With these

commands you can record a bag file, play/replay a file you've recorded, and find information about a bag file.

Let's try recording our first bag file. To do this we'll need three terminals all

running ROS. The first terminal should already have our turtlesim running. If it

isn't running you can restart it with ros2 run turtlesim turtlesim_node. Next

you'll need to start the draw_square demo again to get the default turtle

moving. To do this run ros2 run turtlesim draw_square. Now, in a third

terminal we can bag some data by running the bag command. Let's first look at

the record sub command by running ros2 bag record -h

$ ros2 bag record -h

usage: ros2 bag record [-h] [-a] [-o OUTPUT] [-s STORAGE]

[-f SERIALIZATION_FORMAT] [--no-discovery]

[-p POLLING_INTERVAL] [-b MAX_BAG_SIZE]

[topics [topics ...]]

ros2 bag record

positional arguments:

topics topics to be recorded

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-a, --all recording all topics, required if no topics are listed

explicitly.

-o OUTPUT, --output OUTPUT

destination of the bagfile to create, defaults to a

timestamped folder in the current directory

-s STORAGE, --storage STORAGE

storage identifier to be used, defaults to "sqlite3"

-f SERIALIZATION_FORMAT, --serialization-format SERIALIZATION_FORMAT

rmw serialization format in which the messages are

saved, defaults to the rmw currently in use

--no-discovery disables topic auto discovery during recording: only

topics present at startup will be recorded

-p POLLING_INTERVAL, --polling-interval POLLING_INTERVAL

time in ms to wait between querying available topics

for recording. It has no effect if --no-discovery is

enabled.

-b MAX_BAG_SIZE, --max-bag-size MAX_BAG_SIZE

maximum size in bytes before the bagfile will be

split. Default it is zero, recording written in single

bagfile and splitting is disabled.

We can see from the help file that the syntax for recording a bag is to simply

give the sub command a list of topics to record. Most of the other arguments are

for more advanced users to help configure how and when data is stored. It is

worth noting that there is a -a, --all command that records all the data. You

can also specify the output bag file with the -o, --output command.

Let's go ahead and run our bag command, and let's bag the pose data on the

/turtle1/pose topic and save it to the file turtle1.bag using the -o

flag. Be aware that the program will continue bagging data until you hit

CTRL-C, so give the command a good 30 seconds to collect data before you kill

it.

$ ros2 bag record /turtle1/pose -o turtle1

[INFO] [rosbag2_storage]: Opened database 'turtle1'.

[INFO] [rosbag2_transport]: Listening for topics...

[INFO] [rosbag2_transport]: Subscribed to topic '/turtle1/pose'

[INFO] [rosbag2_transport]: All requested topics are subscribed. Stopping discovery...

^C[INFO] [rclcpp]: signal_handler(signal_value=2)

Now that we collected our data let's inspect our bag file. You can introspect

any bag file using the ros2 bag info command. This command will list the

messages in the bag, the duration of file, and the number of messages.

$ ros2 bag info turtle1

Files: turtle1.db3

Bag size: 268.4 KiB

Storage id: sqlite3

Duration: 68.705s

Start: May 4 2020 16:10:26.556 (1588633826.556)

End May 4 2020 16:11:35.262 (1588633895.262)

Messages: 4249

Topic information: Topic: /turtle1/pose | Type: turtlesim/msg/Pose | Count: 4249 | Serialization Format: cdr

Once you have collected a bag file you can replay the file just like a running system. Bags are a great tool for debugging and testing. You can treat a ROS bag like a recording of a running ROS system. When you play a bag file you can use most of the ros2 CLI tools to inspect the recorded topics.

To replay the bag, first use CTRL-C to turn off the

turtlesim_node and the draw_square node. Now in a new terminal replay the bag

file using the following command:

$ ros2 bag play turtle1

[INFO] [rosbag2_storage]: Opened database 'turtle1'.

Nothing should happen visibly, but a lot is happening under the hood.

To see what is happening go to a second terminal. Just like a running robot,

you should be able to list and echo topics:

$ ros2 topic list

/parameter_events

/rosout

/turtle1/pose

$ ros2 bag info turtle1

x: 3.8595714569091797

y: 3.6481313705444336

theta: -1.2895503044128418

linear_velocity: 1.0

angular_velocity: 0.0

---

ROS2 Component Command

ROS2 Daemon Command

ROS2 Doctor Command

With any complex system problems can sometimes arise, and knowing how to describe your

system and what is happening can do a lot to help others help you fix your

problem. ROS 2 has a doctor command that you can use to print a variety of

reports that you can use to help communicate the state of your system to others

trying to provide help. Whether it is one of your co-workers, a vendor, or an

on-line forum, providing detailed and complete information about your ROS system

can go a long way to solving your problem. Let's call --help on the ROS 2

doctor command:

$ ros2 doctor --help

usage: ros2 doctor [-h] [--report | --report-failed] [--include-warnings]

Check ROS setup and other potential issues

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--report, -r Print all reports.

--report-failed, -rf Print reports of failed checks only.

--include-warnings, -iw

Include warnings as failed checks. Warnings are

ignored by default.

As we can see from the help file we have a couple of report options. One option

is to print the full report with -r, or just what failed with -rf. If you're

running ros2 doctor -r you should see a fairly lengthy report generated giving

information about your computer's operating system, your networking

configuration, and your running ROS system. If you ever run into an issue you

should always include this full report.

ROS 2 Interface

As you've already seen, ROS uses standard messages so that different packages and programs, potentially written in different programming languages, can all talk to one another. To make this all work, ROS uses standard messages, and communication protocols built on top of those standard messages. This can make finding type information about a particular message, service, or action difficult. To help developers write both CLI command calls and develop client code, the ROS CLI has the interface command. We've touched on this command briefly in other sections, as it is the go to tool for message type information.

To better understand the interface command let's start by looking at its high

level help command to see what sub commands are available:

$ ros2 interface --help

usage: ros2 interface [-h]

Call `ros2 interface <command> -h` for more detailed

usage. ...

Show information about ROS interfaces

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

Commands:

list List all interface types available

package Output a list of available interface types within one package

packages Output a list of packages that provide interfaces

proto Output an interface prototype

show Output the interface definition

Call `ros2 interface <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

The interface command are all geared towards helping you understand

available message types. Let's examine the list sub command in depth. list

will list all of the available messages, services, and actions on your

system. This command has flags that can help you narrow down the scope of your

search. Even a basic ROS installation has a lot of messages, so a tool you

should get familiar with is grep. grep lets you search through some text to

find what you are looking for quickly and easily. You can grep in a case

insensitive manner using the -i flag followed by the text you want to search

for. We can tie this CLI tool to our interface tool by using the UNIX pipe operator |. The example below

shows you how to use the list operation and then how to use it to search:

$ ros2 interface list --only-msgs

Messages:

action_msgs/msg/GoalInfo

action_msgs/msg/GoalStatus

... <DOZENS OF DIFFERENT TYPES> ...

visualization_msgs/msg/MarkerArray

visualization_msgs/msg/MenuEntry

$ ros2 interface list --only-msgs | grep -i point

geometry_msgs/msg/Point

geometry_msgs/msg/Point32

geometry_msgs/msg/PointStamped

map_msgs/msg/PointCloud2Update

pcl_msgs/msg/PointIndices

rcl_interfaces/msg/FloatingPointRange

sensor_msgs/msg/PointCloud

sensor_msgs/msg/PointCloud2

sensor_msgs/msg/PointField

trajectory_msgs/msg/JointTrajectoryPoint

Using grep to search through CLI output is a common tactic used by developers to

find just the specific information they need. The next two sub commands

package and packages can be used to first determine what ROS packages are on

your system, and then to drill down into an individual package to determine what

messages are in that package. Note that

you can use grep just like before to search for your specific interest. The

example below shows you how to first determine if std_msgs is installed and

then to find out what sort of array types it contains:

$ ros2 interface packages

action_msgs

action_tutorials_interfaces

actionlib_msgs

builtin_interfaces

composition_interfaces

diagnostic_msgs

example_interfaces

geometry_msgs

lifecycle_msgs

logging_demo

map_msgs

nav_msgs

pcl_msgs

pendulum_msgs

rcl_interfaces

rosgraph_msgs

rqt_py_common

sensor_msgs

shape_msgs

std_msgs

std_srvs

stereo_msgs

tf2_msgs

trajectory_msgs

turtlesim

unique_identifier_msgs

visualization_msgs

kscottz@kscottz-ratnest:~/Code/ros2multirobotbook/src$ ros2 interface package std_msgs | grep -i array

std_msgs/msg/Int8MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/Int32MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/MultiArrayLayout

std_msgs/msg/UInt64MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/Float32MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/UInt16MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/UInt32MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/Int16MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/ByteMultiArray

std_msgs/msg/Int64MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/Float64MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/UInt8MultiArray

std_msgs/msg/MultiArrayDimension

The next two commands are particularly

helpful and you should remember them as they will make your life much easier. As

we have discussed previously all message publication, service calls, and action

calls in the CLI take in both the message type and data you want to transmit in

YAML format. But what if you don't know the message format, and you don't know a lot about

YAML? The interface show and interface proto commands make this process

easier by respectively telling you first the message type and then the message

format. Recall earlier in the chapter when we called the spawn service on

our turtle simulation. We can use interface show to tell us broadly about the

service and what each of the values mean. We can then use interface proto,

short for prototype, to then generate an empty message that we can fill

out. See the example below:

$ ros2 interface show turtlesim/srv/Spawn

float32 x

float32 y

float32 theta

string name # Optional. A unique name will be created and returned if this is empty

---

string name

$ ros2 interface proto turtlesim/srv/Spawn

"x: 0.0

y: 0.0

theta: 0.0

name: ''

"

$ ros2 service call /spawn turtlesim/srv/Spawn "{<copy and paste proto here>}"

You can see from the example above how handy these tools can be. It is worth

noting that you need to paste the prototype into a set of quotes and curly

braces for the call to work "{<prototype>}".

ROS 2 Launch

The launch command is used to run ROS launch files. Up until this point we've

been running single ROS programs by hand using the run command, however this

is not how larger ROS systems are generally operated and many robots command

tens if not hundreds of small programs. The ROS launch command is different from

most of the other ROS commands in that it has no sub commands and has a single

function, to start a ROS launch file that executes multiple of programs.

To illustrate this command let's take a look at

its help file.

$ ros2 launch -h

usage: ros2 launch [-h] [-d] [-p | -s] [-a]

package_name [launch_file_name]

[launch_arguments [launch_arguments ...]]

Run a launch file

positional arguments:

package_name Name of the ROS package which contains the launch file

launch_file_name Name of the launch file

launch_arguments Arguments to the launch file; '<name>:=<value>' (for

duplicates, last one wins)

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-d, --debug Put the launch system in debug mode, provides more

verbose output.

-p, --print, --print-description

Print the launch description to the console without

launching it.

-s, --show-args, --show-arguments

Show arguments that may be given to the launch file.

-a, --show-all-subprocesses-output

Show all launched subprocesses' output by overriding

their output configuration using the

OVERRIDE_LAUNCH_PROCESS_OUTPUT envvar.

Launch files are usually included with a ROS package and are commonly stored in a

launch sub directory. Modern launch files are usually written in Python and end

with the *.launch.py file extension. The launch command has two arguments,

the first one is the package name and then the launch file name. If you are unaware

of the launch files in your package you can use tab completion to list all the

available launch files. Finally, some launch files have arguments that can be

appended to the command. If you are unsure about what a launch file does, or

what arguments it needs, the --print and --show-args commands will tell you

this information. Let's read up on the multisym.launch.py launch file and then

run it following the example below (end the simulation with CTRL-C):

$ ros2 launch turtlesim multisim.launch.py --show-args

Arguments (pass arguments as '<name>:=<value>'):

No arguments.

$ ros2 launch turtlesim multisim.launch.py --print

<launch.launch_description.LaunchDescription object at 0x7f75aab63828>

├── ExecuteProcess(cmd=[ExecInPkg(pkg='turtlesim', exec='turtlesim_node'), '--ros-args'], cwd=None, env=None, shell=False)

└── ExecuteProcess(cmd=[ExecInPkg(pkg='turtlesim', exec='turtlesim_node'), '--ros-args'], cwd=None, env=None, shell=False)

$ ros2 launch turtlesim multisim.launch.py

[INFO] [launch]: All log files can be found below /home/kscottz/.ros/log/2020-06-24-14-39-03-312667-kscottz-ratnest-20933

[INFO] [launch]: Default logging verbosity is set to INFO

[INFO] [turtlesim_node-1]: process started with pid [20944]

[INFO] [turtlesim_node-2]: process started with pid [20945]

^C[WARNING] [launch]: user interrupted with ctrl-c (SIGINT)

ROS 2 Lifecycle

ROS 2 has a new feature called lifecycle which allows for greater control over

the state of a ROS node. Roughly, this feature allows nodes to have complex

start-up and shut-down procedures that are correctly handed. An example of such

a node would be one that controls a sensor or actuator that needs to perform a

power-on self-test or calibration procedure prior to running. The ROS design

docs

give a great primer on the states and transitions in a lifecycle

node. Let's look at the

lifecycle command to determine what sub commands are available:

$ ros2 lifecycle -h

usage: ros2 lifecycle [-h]

Call `ros2 lifecycle <command> -h` for more detailed

usage. ...

Various lifecycle related sub-commands

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

Commands:

get Get lifecycle state for one or more nodes

list Output a list of available transitions

nodes Output a list of nodes with lifecycle

set Trigger lifecycle state transition

Call `ros2 lifecycle <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

The nodes sub command will list all the lifecycle nodes on a given system.

Once you have listed the nodes, you can list each node's available

transitions using ros2 lifecycle list <nodename>. These transitions are

dictated by the node's current state with some states having more transitions

available than others. If instead of available transitions you wish to query the

current state you can use lifecycle get to return the current state of

your target node. Once you have satisfactorily determined the state of the node

and the available transitions, the lifecycle set command can be used to trigger

the node to transition to a new state. Generally, these CLI commands are used to

diagnose failure modes of systems, or to manually transition a particular

component.

ROS 2 msg (Message)

ROS 2 Eloquent is the last version of ROS to use the msg command. All of the

commands in msg are mirrored in the interface command. These features are

currently deprecated and will be removed in Foxy.

ROS 2 pkg (Package)

The ROS 2 package command is a very useful command to understand what ROS

packages are installed on your system, where they are installed, and the

executables contained within each package. These tools are particularly useful

for understanding an existing robot configuration and finding tools that are

only used on occasion. Let's start by taking a look at the help file for the pkg command:

$ ros2 pkg -h

usage: ros2 pkg [-h] Call `ros2 pkg <command> -h` for more detailed usage. ...

Various package related sub-commands

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

Commands:

create Create a new ROS2 package

executables Output a list of package specific executables

list Output a list of available packages

prefix Output the prefix path of a package

xml Output the XML of the package manifest or a specific tag

Call `ros2 pkg <command> -h` for more detailed usage.

This command has a variety of sub commands, many of which should look fairly

familiar at this point. The list sub command acts in a manner very similar to

list sub commands we have discussed previously, but this one only lists the

installed system packages. This sub command is often used with grep to help you

find out if a particular package is installed.

Once you have located an installed package you can then have it list the

executables contained by the package using the executables command. This is

much more practical than finding the executables manually. The sub command takes

in a single argument which is the package name. The executables command has a

single optional argument, --full-path, which will output the full path to all

the executable programs. The example below shows how to use these

commands to check the path for all of the turtlesim executables:

$ ros2 pkg list | grep turtle

turtlesim

$ ros2 pkg executables turtlesim --full-path

/opt/ros/eloquent/lib/turtlesim/draw_square

/opt/ros/eloquent/lib/turtlesim/mimic

/opt/ros/eloquent/lib/turtlesim/turtle_teleop_key

/opt/ros/eloquent/lib/turtlesim/turtlesim_node

If you just wanted to know the path to the turtlesim executables you could use

the prefix sub command, which returns the path for a given package's

executables.

Each ROS package contains an XML file that contains metadata for the package,

including information such as the license, maintainer, and its dependencies. ROS

pkg has a handy xml sub command to print these files to the screen, saving you

the hassle of locating and opening the file. You can use grep on the output of

this command to get just the info you need. Below is an example of xml and prefix used to find

the directory of turtlesim, its maintainer, and its license:

$ ros2 pkg prefix turtlesim

/opt/ros/eloquent

$ ros2 pkg xml turtlesim | grep maintainer

<maintainer email="dthomas@osrfoundation.org">Dirk Thomas</maintainer>

$ ros2 pkg xml turtlesim | grep license

<license>BSD</license>

kscottz@kscottz-ratnest:~$

The last sub command in the pkg command is create. create is a tool to help

you create a ROS package. We'll use this sub command later in the chapter to

create a new ROS package. The short of it is that you feed the command your

package name and all of the relevant information for your package as optional

arguments.